Salmonella

Discovered by Daniel E. Salmon over 100 years ago, Salmonella are facultative anaerobic rod-shaped bacteria that can cause a food borne infection in humans. There are many different serotypes of Salmonella. In the United States, Salmonella serotype Enteritidis, Salmonella serotype Newport and Salmonella serotype Typhimurium are the most common and account for half of all human infections. Salmonella infections cause more hospitalizations and deaths than any other food pathogen, and over one million Americans are estimated to contract salmonellosis every year from consuming contaminated food[1].

Incidence in meat and poultry

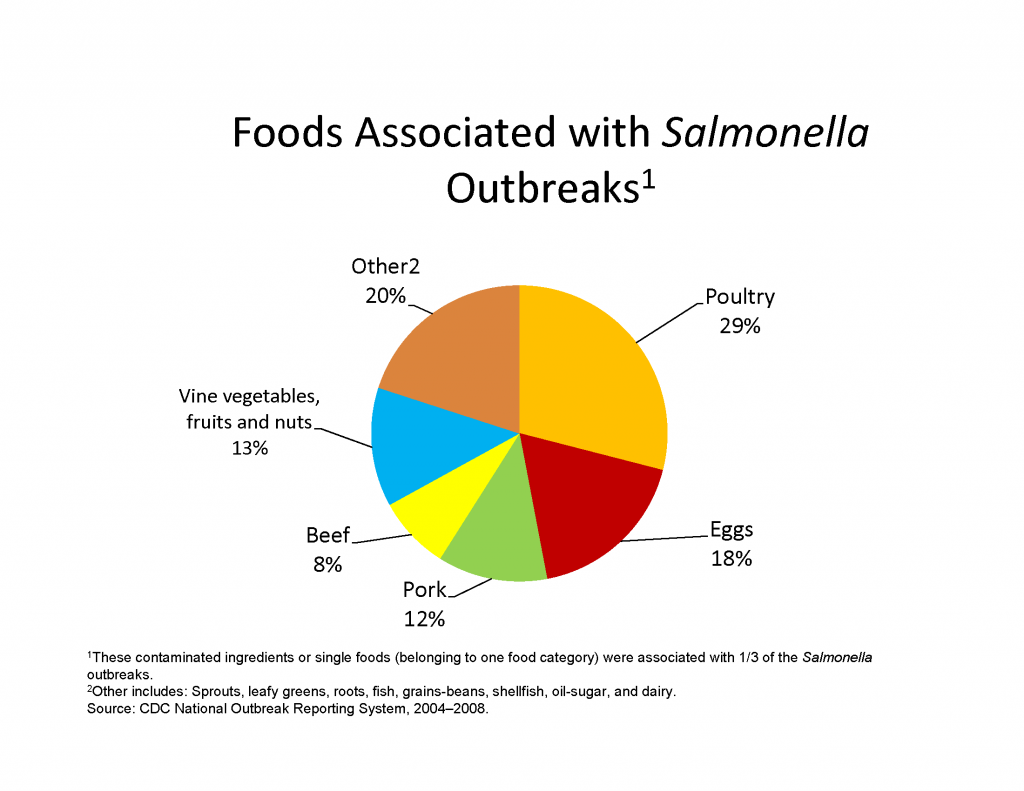

Salmonella live in the intestinal tracts of humans and animals and can be transmitted by contaminated feces on food. Animals that carry Salmonella can pass it in their feces that then can easily contaminate their bodies and their surroundings. Salmonella is contracted by coming into contact with these infected animals or their surroundings; or consuming contaminated food or water. Most domestic animals including chickens, cattle, pigs, dogs, and cats have been found to carry the bacteria. But other healthy-appearing animals can also pass Salmonella to people such as reptiles, amphibians, guinea pigs, hamsters, birds, horses, and other farm animals. Foods such as meat, fish, poultry, eggs and dairy products are most susceptible to Salmonella contamination, but care should also be taken with items such as fruits, vegetables, peanut products, cream, dressings and raw or unpasteurized milk. The organism also survives well on low-moisture foods, such as spices, which have been linked to outbreaks. S. enteritidis can survive inside eggs thus creating additional challenges with respect to shell eggs.

While some recent media reports may claim that “Kosher,” “free-range,” “organic,” or “natural” chickens have lower incidence rates of Salmonella, there is not any valid scientific information that shows that the prevalence of Salmonella is affected by the production system.

Incidence of illness

Depending on the serotype, Salmonella can cause two types of illness including nontyphoidal salmonellosis and typhoid fever. The symptoms of nontyphoidal salmonellosis are diarrhea, fever, nausea, vomiting and abdominal cramps 12 to 72 hours after exposure. The illness lasts four to seven days and with standard cases should not render hospitalization, but serious cases may require antibiotics and treatment by a physician if deemed necessary. Although the infective dose is usually only a relatively small number of bacteria, the amount ultimately depends upon the age and health of the host. The elderly, immunocompromised and young children (under the age of 5) are most susceptible to contract a serious case of the illness. Also, it has been reported that arthritis problems can follow some cases.

Typhoid fever is more serious and has a higher mortality rate than nontyphoidal salmonellosis, but cases are drastically less common. Typhoid fever is caused by serotypes S. Typhimurium and S. Paratyphimurium A, both of which are found only in humans. Since these serotypes are found only in human hosts, the sources of these organisms in the environment can be drinking water or irrigation water contaminated by untreated sewage. Symptoms such as high fever, lethargy, gastrointestinal symptoms, headache, achiness and loss of appetite may occur within one to three weeks, but may be as long as 2 months after exposure. Typhoid fever generally lasts about two to four weeks. Septicemia, septic arthritis, and a chronic infection of the gallbladder may follow serious cases.

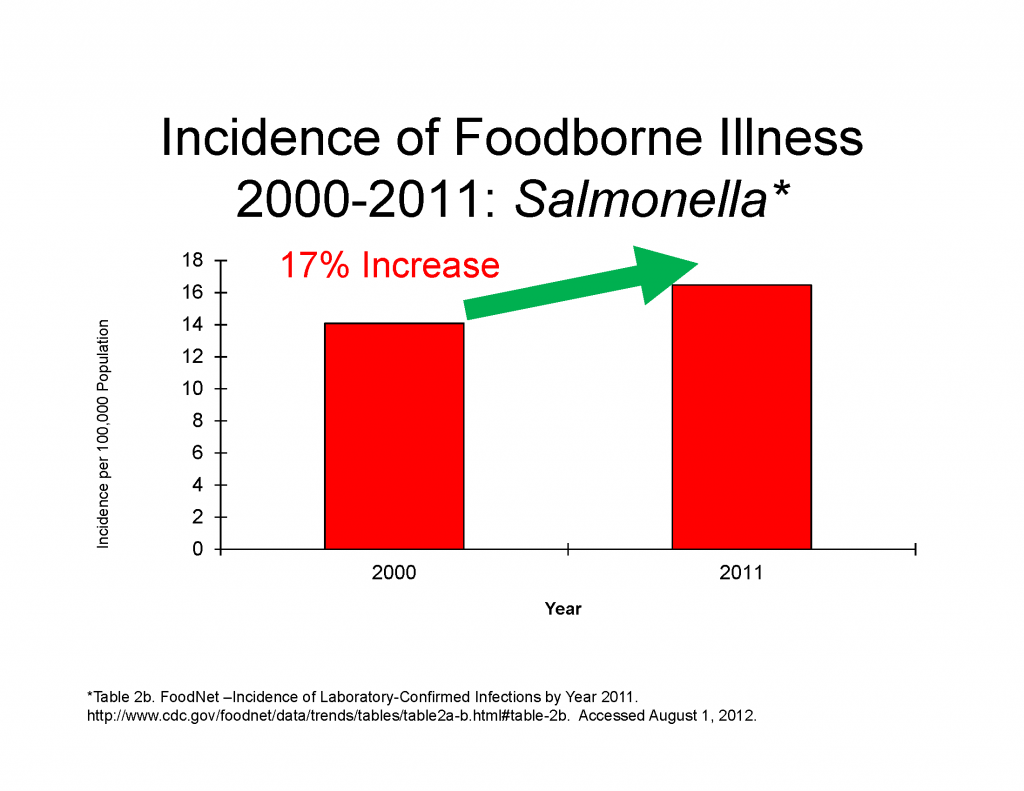

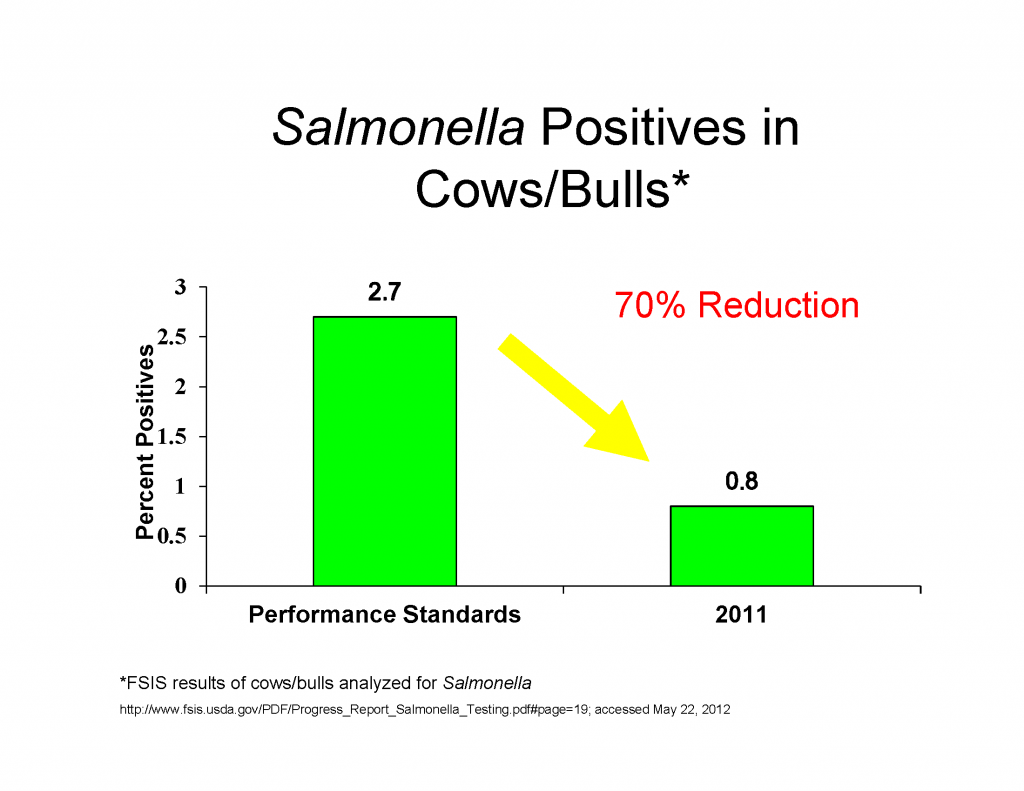

Illnesses attributed to Salmonella have remained virtually stagnant since 1996 and have actually increased 17% since 2000. This is even more disturbing, as the scientific regulatory data for meat and poultry indicate decreases in Salmonella positives. Since there are less Salmonella positives and a higher percentage of illnesses, multiple steps along the farm to the table chain will require strong action to reduce Salmonella infection. Farmers, the food industry, regulatory agencies, food service, consumers, and public health authorities all have a role.

Government oversight

The Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) is the public health regulatory agency in the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) responsible for the safety of the nation’s commercial supply of meat, poultry and egg products. FSIS inspectors ensure establishments are meeting standards by collecting randomly selected product samples and sending them to an FSIS laboratory for Salmonella analysis. Beginning in 1996, FSIS implemented a new plan for meat and poultry inspection called HACCP (Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point). HACCP is a regulatory program that focuses on controlling food safety hazards at different steps in the process. HACCP programs are designed to exert control over a variety of microbial pathogens, including Salmonella.

Preventing infection

Salmonellosis is more common in the summer months, as the warmer environment is more desirable for the survival of bacteria in food. The general rule is to keep hot foods hot and cold foods cold. It is very important to store leftovers in a cool environment within two hours after eating or one hour after eating on a particularly hot day (90° F or higher). It is also recommended for people to wash hands thoroughly immediately after handling any animals or birds, including reptiles.

Prevent cross-contamination in the kitchen by using separate cutting boards for foods of animal origin and other foods. Carefully clean all cutting boards, countertops and utensils with soap and hot water after preparing raw foods. Wash hands with hot, soapy water before and after handling raw foods of animal origin. Avoid consumption of non-pasteurized milk and untreated surface water. Make sure that persons with diarrhea, especially children, wash their hands carefully and frequently with soap to reduce the risk of spreading the infection. Wash hands with soap after having contact with pet feces.

Consumers should always follow the safe handling practices detailed on every package of raw meat and poultry and should take special care to cook ground meat products, such as hamburger and meat loaf, to an internal temperature of 160°F and ground poultry to 165°F. Beef products like steaks or roasts can be cooked with 145°F with a three-minute rest period. What is a rest period? It is the minimum time after you remove the meat product from the heat source (oven, grill, broiler, etc.) before you may eat the product. Temperature is best verified using an instant-read thermometer.

Why are there two different recommended cooking temperatures? Whole muscle cuts like steaks and roasts are sterile on the inside. Cooking the products destroys any bacteria present on the outside of these cuts. However, when meat is ground, any external bacteria that may be present are distributed throughout the ground product. That is why it is so important to ensure that ground beef products are thoroughly cooked to 160°F and ground poultry to 165°F.

Consumers with food safety questions should visit www.meatsafety.org to learn more about safe food handling, or call USDA’s Meat and Poultry Hotline at 1-888-674-6854.

Helpful links

- American Meat Institute

- Meat Safety

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- American Meat Science Association

- American Society for Microbiology

- Institute of Food Technologists

- Food Safety Inspection Service

Third-Party Experts

Gary Acuff, Ph.D.

Professor and Head, Department of Animal Science

Texas A&M University

(409) 845-4402

gacuff@tamu.edu

[1] CDC. 2011. Vital Signs: Incidence and Trends of Infection with Pathogens Transmitted Commonly Through Food — Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network, 10 U.S. Sites, 1996–2010. MMWR. 60(22);749-755. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6022a5.htm. Accessed May 21, 2012.